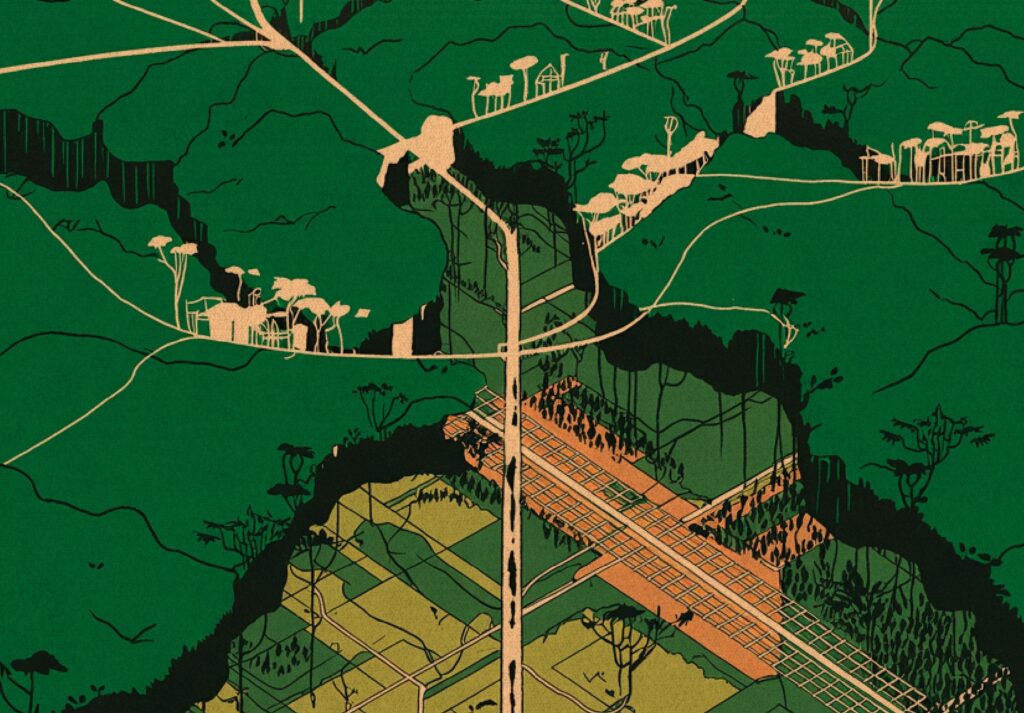

Study reveals that infrastructure investments in the region still ignore its social and environmental complexity — and risk repeating past mistakes

By Gustavo Nascimento

The Amazon is once again at the center of federal investment discussions with the launch of the new Growth Acceleration Program (PAC). Promising economic growth, social inclusion, and decarbonization, the program has been marketed as a cornerstone of national development — especially for the Amazon region. But are these projects truly prepared to meet the challenges of Brazil’s most strategic territory?

A study published by the Climate Policy Initiative at PUC-Rio, in collaboration with the Amazônia 2030 project, titled “The Amazon in the New PAC: Recommendations to Drive Sustainable Infrastructure”, brings this into question — and delivers an uncomfortable truth: we’re still not getting it right.

The study finds that while the New PAC includes investments for all nine states of the Legal Amazon, its proposals fall short of addressing the region’s actual priorities. Critical areas like sanitation and digital connectivity remain largely neglected. The logic driving project selection hasn’t changed either — still favoring large-scale construction projects disconnected from the daily lives and needs of local communities. Even worse, the forest once again risks being treated as an obstacle to development, rather than as a vital national asset.

The PAC also overlooks the Amazon’s deep social and environmental complexity. It fails to acknowledge concepts such as the Five Amazons, which highlight the vast internal diversity across the region’s social, economic, and ecological landscapes. A highway in Roraima has profoundly different consequences than a port in Amapá — yet the PAC continues to treat the entire region as one homogeneous, sparsely populated frontier waiting to be “developed.”

What’s more, the program isn’t meaningfully aligned with other key federal policies, such as the PPCDAm (Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon) — Brazil’s main strategy to combat deforestation. This lack of integration weakens the coherence of government efforts and undermines the country’s credibility in global negotiations, including COP30, which will take place in Belém in 2025.

But there are viable — and urgent — alternatives. The study proposes clear, actionable recommendations to bring investments in line with on-the-ground realities: infrastructure projects tailored to local contexts, coordination with conservation efforts, governance with genuine community participation, and prioritization of basic sanitation, digital inclusion, and clean energy. Rather than large, high-impact megaprojects with limited benefit, Brazil could pursue decentralized, inclusive, and regenerative infrastructure solutions.

The first step is to accept that there is no single “Amazon.” The territory is vast, diverse, and marked by deep inequality. Any sustainable development plan must begin with that understanding. Brazil urgently needs a regional strategy for the Amazon — one that can guide national programs with a grounded view of the territory’s different settlement patterns, land uses, and realities. This strategy should also confront longstanding gaps in healthcare, education, sanitation, and mobility.

Moreover, national planning tools like the National Logistics Plan (PNL) must adopt a tailored vision for the Amazon. That includes explicit socio-environmental criteria for project selection, serious consideration of climate and social risks, and rigorous impact assessments.

Linking infrastructure efforts with existing environmental policies — like the PPCDAm — is not only logical but overdue. Public works should reinforce Brazil’s deforestation targets, not contradict them. Strong speeches for the global stage won’t suffice — what’s needed is transparency, good governance, and consistent public monitoring. This means sharing clear information about how projects are chosen, what impacts are expected, whether they’re environmentally viable, and how local communities are being heard.

From a sectoral perspective, logistics infrastructure can be expanded with less socio-environmental harm if focused on already-altered landscapes like the so-called “Deforested Amazon,” where over 70% of original forest cover has already been lost. In these areas, investments can improve supply chains, expand access to essential services, and reduce migration pressures on still-intact forests. In contrast, infrastructure projects in the “Forested” and “Under-Pressure” Amazon — where vegetation remains abundant or threatened — must meet stricter technical, economic, and environmental standards, with in-depth evaluation of both direct and indirect impacts. In these places, infrastructure must become a partner — not a threat — to conservation.

Digital connectivity must move forward urgently, bringing internet access to remote communities and mid-sized towns that are currently overlooked. When it comes to sanitation, efforts should target the most underserved municipalities — such as those in Amapá — using simple, cost-effective solutions like decentralized septic systems.

Finally, the Amazon’s energy transition cannot rely on fossil fuels like diesel or natural gas. Instead, the PAC should promote the installation of solar and wind power systems and strengthen distributed generation using renewables — cleaner and more economically viable options for remote areas. These solutions are compatible with existing initiatives like Luz Para Todos (Brazil’s universal electricity access program) and ANEEL regulations.

In the Amazon, development can no longer be a euphemism for destruction. The region is not an “empty space” to be filled — it is a vibrant, complex society that must be respected. Brazil now has an opportunity to do things differently. Investing in the Amazon sustainably isn’t just a historic responsibility — it’s a strategic choice. There’s no excuse to keep investing in outdated models when the future is already within reach.

Gustavo Nascimento is a Black journalist, jiu-jitsu black belt, and project coordinator at O Mundo que Queremos.

Foto: Road cutting through forest in the Amazon/Marcelo Camargo/Agência Brasil